My high school years were absolute shit. I was an all-state trumpet player and mathlete, but the only real highlight for me was the senior prom after-party where I smoked pot for like, the third time in my life, with a kid I hadn’t seen since elementary school as we proceeded to talk about our Pokemon club in third grade. I never got as messed up ever again in my life as I did at that party and the various graduation parties after. They were never about socializing for me, they were purely and completely about getting fucked up for free and with the help of some really irresponsible adults.

When the parties ended and high school ended, I was left at home with no similar outlet, however unhealthy and destructive that outlet might have been. One day I broke down and explained how empty I felt to my mother and a few years of therapy went a long way. The other stories I have—the worst ones, the ones we all have about when we were at our most lonely and vulnerable—still aren’t anywhere near the experiences of so many others. Still, I can tell you honestly that I believe I am lucky to be here.

The world didn’t end. But it was close. The psycho-sexual existential lurch comprised by the chemical warfare occurring in a teenager’s brain is The Formative Thing for us. And, for me, without parents that were as supportive, it is quite literally not something I would have survived.

Sacred Heart takes us to a world that is identical to ours. The kids in this book are just that: kids. The one differences is that, at some point, you realize that none of their lives are circumscribed by responsible adults; or, you know, by any adults. The truly unchecked flare-ups in teen angst are not cute and unfortunate, but monstrous, tragic, and sad. What’s worse is that without any guidance at all, the tragic does not even register as such with these teens.

Maybe some of that has something to do with the cultishness instead of the outright lack of adults. But make no mistake, even within the confines of this cult, the cult itself is fundamentally changed by its lack of adults. It becomes a cult of angst alone, which looks much less like selfies, votes for Bernie Sanders, and--I don’t know, however else young kids are stereotyped these days—and more like a mix of cliche sex in parked cars and, oh, you know, dead bodies all over the fucking place. Sacred Heart is a mix of horror story and a really great, really straight-shooting coming of age high school drama. These kids won’t, in fact, be alright, but god damnit even in this intensely fucked up reality, they’re sort of managing.

|

| Voices literally fade into the background as Empathy focuses in on approaching the cute lead singer. |

A huge part of this… what’d I call it? Yes, the “psycho-sexual existential lurch” of teenagery— a huge part of that is not what happens to us but the intensity and pure novelty with which we experience the things that happen to us. Seeing the boy across the room as a pure visual story beat is actually really fucking uninteresting. Even if every reader knows that it’s a big character moment because of how similar situations felt to them, the goddamn book isn’t about the reader’s experience. (Now, cut me some slack: sometimes it very well is, as I have talked about before). Suburbia is constantly interested in driving the point home. At moments where she could let the reader do the work and lose very little, she instead gains a lot with some clever choices.

|

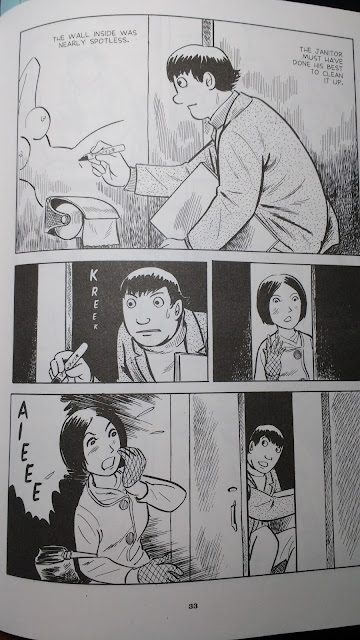

| LOOK AT THIS PAGE |

At another point, Ben confronts her friend-with-benefits Otto about wanting to forego any further sexual encounters in favor of saving their friendship, making for an obviously awkward encounter. The well-paced, flowing visual narrative of Sacred Heart comes to a grinding halt, begetting nine-panel grids of awkward back and forth between the star-crossed not-lovers-but-sort-of-lovers-but-mostly-friends. And you’ve had these conversations: the ones where everything else drops away and it’s just you and another person and it’s just gut-wrenchingly hard to say what you planned on saying because the other person is making it as hard as possible for you, or at least it seems that way because of the hours you spent having a pre-meditiated version of this conversation alone in the dark with some weirdly idealized imaginary version of your interlocutor.

And there’s even more to like about this book. I adore how often Suburbia injects two or three panel moments of innocence into what is really a grim story. I would read a comic strip by her in a *snap*, which isn’t something I often come away from such a long, substantial work saying. There’s a chapter in the middle told from the dog’s perspective, and not in the incredibly convuluted Pizza Dog way but in the sense of literal perspective. Interestingly enough, that chapter is the heaviest with a sense of foreboding and something being amiss: the lack of caregivers is face-punchingly obvious when the story is shifted to the perspective of the one character in the story who actually has a caregiver. It’s just such a mature, big-picture storytelling choice. Another of my favorite things throughout the book is the way that Suburbia juxtaposes rigid depictions of light with flowing, ethereal depictions of both light and sound.

I could go on and on, but honestly this is one of those great books where I want to open up to a sequences and shove it in a friend’s face and yell “LOOK AT WHAT SHE DID HERE. DO YOU SEE THIS.” I was on such a comic-high coming off of A Drifting Life (which I did write about, by the way, but my essay is such a behemoth that it needs a lot of work) that whatever came next had to be good. And goddamn this book was good.