Usually when I write something, I like to focus in on a particular thing and if I happen to wander into some concentric topical circles, then that’s OK. Writing about Yoshihiro Tatsumi has proven to be a slightly more complicated task. I made the mistake (not that it hasn’t been a pleasant and interesting one) of reading Abandon the Old in Tokyo, a compilation of Tatsumi’s shorter works, at the same time as A Drifting Life, a beat-up-somebody-without-leaving-bruises length autobiography. I could give you any amount of historical context for Tatsumi’s notable and historically important approach to storytelling in comics; however, since Holmberg has already written on this, any attempt by me to contextualize gekiga or Tatsumi any better would be in vain.

Actually, that’s not true: some guy fucks a dog in one of these stories (not the autobio). Does that paint a picture for you? Yes? Ok. There you go.

Perspicuous as fuck.

Previously, I have written about one of Tatsumi’s contemporaries, Tadao Tsuge. The two share important similarities in the themes they tackle, and the intersection of those similarities is really the heart of what gekiga was trying to accomplish. These shorter stories from each author, often seen in the alt-manga publication Garo, are almost always deeply Japanese. It is impossible to separate most of these stories from their taking place in post-war Japan. Perhaps you can draw connections to broader themes (as I did when I was ranting about Tsuge and Hume), but even when a story is about a search for identity in society, it is very specifically in that society at that point in its history. Tsuge’s story about the man who vanishes is most felicitously considered as being reflective of a real missing persons problem at that period in Japanese history. Similarly, when the twisted steel and concrete of the city imposes itself on Tatsumi’s characters, it is not just a general statement about men finding their place in a cold world: it is always wrapped tightly in the chaotic, often depressing cocoon of post-war Japan.

What blows me away about Tatsumi is how he succeeds in accomplishing the same kinds of deep dark themes as Tsuge while playing his stories entirely realistic and straight. Tsuge’s pages are ethereal, and the stories typically play out somewhere between the shadows and the people themselves, with inanimate objects often acting as mere extensions of the persons being drawn. For Tatsumi, however, people are placed firmly in reality and goodness gracious what a reality it is.

Tatsumi achieves the darkness of a story by letting things play out in a fucked up way. It’s sort of shockingly simple, but it’s not something many artists were doing before Tatsumi. I want to avoid overstating his influence, since many folks who eventually figured out they could do this with comics likely had no exposure to his work, but that doesn’t take anything away from his accomplishments as a storyteller.

Unlike many other artists exploring the dark corners of the ways in which humans deal with living amongst each other, Tatsumi does not marry us to visual metaphors. He draws much more from the dark, unseen internal motivations of his characters. His stories are not loaded with captions and, in some stories, the main character rarely speaks at all. Tatsumi knows that if he writes just a weird enough story, the darkness will make its way through to the reader with fairly minimal effort

A balancing act ensues with this approach to telling a story. The story must be simultaneously extraordinary and everyday. Tsuge reached this balance by honing in, almost pedantically, on one particularly normal thing—say, an encounter with a friend you haven’t seen in awhile, or some reporters interviewing a guy about his disappearance—and then surrounding that painfully simple thing with absurd visual asides. Tatsumi similarly leans on absurdity; however, he works hard to find the absurdity in the mundane. For instance, “The Washer” revolves around a man who, through a window he is cleaning, finds his daughter caught up in a love affair with her boss. An absurd situation, yes, but one that is at least nomologically possible as presented on the page: it could happen and, if it did, this is what it would look like.

The obtuse aspects of the story are not mysterious, conceptually thick visuals. Instead, the reader will find themselves being rapped on the eyes by the blunt end of realistically shitty situations. In the titular “Abandon the Old in Tokyo,” a man who just wants to spend time with his fiancée without worrying about his elderly mother finds himself desperately carrying the body of his dead abandoned mother through the streets. Tatsumi’s story formula is to take these simply relatable but inherently complex real life situations and then realize something approximating the reader’s worst fears at the very end. Sometimes, as in “The Washer,” these fears are darkly comical; other times, as in “Abandon the Old,” they are powerful and tragic.

Tsuge liked to visually demonstrate people losing their humanity. In Abandon, Tatsumi is much more interested in the essential but secondary bestal nature of man. Stories that aren’t centered around the omni-present gekiga theme of sexual humiliation show characters being lowered to the level of animals, either by acting like them or by, erm… dog sex. The loss of humanity is something that happens in the company of fellow humans, but is shown explicitly as a descent from whatever the human was before.

To me, that’s where Tatsumi shines. I didn’t like Abandon the Old in Tokyo as much as A Drifting Life, and found it wanting in a lot of ways. However, when you keep seeing this descent from human to animal in Tatsumi’s work, there’s a point at which you have to find yourself asking, “okay… but what were they before? What is it that placed us above the monkeys and the dogs and the eels such that these stories characterize a descent from some higher place?”

Nothing. Tatsumi’s answer in these stories assumes no separation! There is an inevitability to these stories such that the ending is not a demarcation of the character’s final descent: it’s a curtain being pulled back as to what they were all along. Though the character who fornicates with the dog claims that he wanted to hang on to the last bit of his dignity after forfeiting it, the manner in which Tatsumi presents the story makes it clear that this character could not get lower. He only appears lower, finally, in the eyes of others, than he was before. But as a person, very little has changed.

I mean, fuck, let’s be serious here: a person who is inclined to have sex with a dog—a person who is even in possession of that disposition in some robust sense—is probably at rock bottom in some way already. Is there a meaningful loss of humanity still awaiting that person? Tatsumi argues, quite reasonably, no.

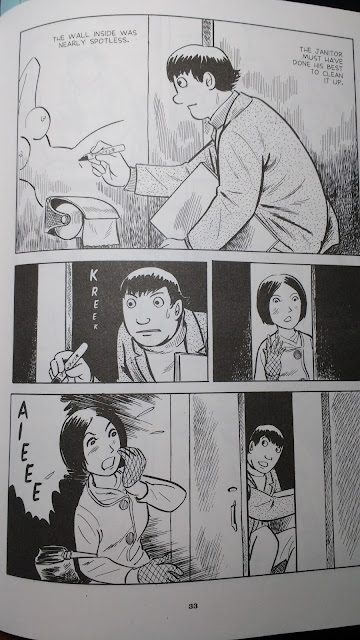

"Unpaid" (the dog story) is a good example for this because of the main character’s own reflection that he wanted to hold onto the last of his dignity: the fact of the matter is, there was very little of substance to be lost. The first story in the book, "Occupied," underscores this. The main character is clearly a pretty harmless pervert, like most of us are. Yet he makes this decision to draw a naked woman on a bathroom stall and through the fact that everyone starts calling him out on it we are supposed to believe that he has somehow descended into the dregs of society. "Occupied" is more about sexual humiliation than loss of humanity, but there's a common thread of some kind of dignity being lost by someone in some substantial way throughout all of these stories.

Tatsumi’s storytelling embraces the reality that his art depicts. We are unambiguously inhabitants of a modern society; a garbage-filled, over-populated, smoggy swamp that locks us by the ankles in its filth at birth (it should not be lost on the reader, by the way, that the one somewhat comedic moment in this whole book involves a newborn being dragged into this crap). The only difference between people is the that some decisions quicken our descent into darkness.

If Abandon the Old in Tokyo isn’t nihilistic, then it is a series of questions that roughly equate to, “but what am I to do?” in the face of a familiar series of desperation-inducing problems. I don’t fault Tatsumi for not answering, but by the end of the book I at least wish he asked a different question once or twice.

Next week: I’m going to write about A Drifting Life, Tatsumi’s autobio and really just a genuinely lovely book; tremendously uncynical.

No comments:

Post a Comment